The Sweet History of Rockwood & Co.

If you’ve studied Warren Buffett, you’ve likely come across the cocoa arbitrage story involving Rockwood & Company. Maybe it’s where you first heard of Jay Pritzker. While it’s a great story, and one we will cover, there’s a lot more to Rockwood’s history.

The company was transformed from a struggling chocolate manufacturer into an investment holding company, and was crucial to building two of the Pritzker family’s most iconic companies: Hyatt and Marmon.

While Jay Pritzker had been doing deals for several years by the time the Rockwood situation came around, Rockwood was the first deal that gave Jay excess capital to reinvest.

What follows is far from exhaustive. It’s more of a scatter plot. Given the importance and complexity of Rockwood’s history (it’s intertwined with basically everything), it would be impossible to cover it all in one article. And there’s a lot I haven’t found yet.

But it’s a good roadmap of some places we’ll go and deals we’ll break down in the future.

It will take a while before I can put together a profile on Jay Pritzker like I did on Nicholas Pritzker. So, if you’re unfamiliar with who Jay is or want to hear more, a good friend of mine recently released a great podcast episode covering him. You can check it out here.

Background

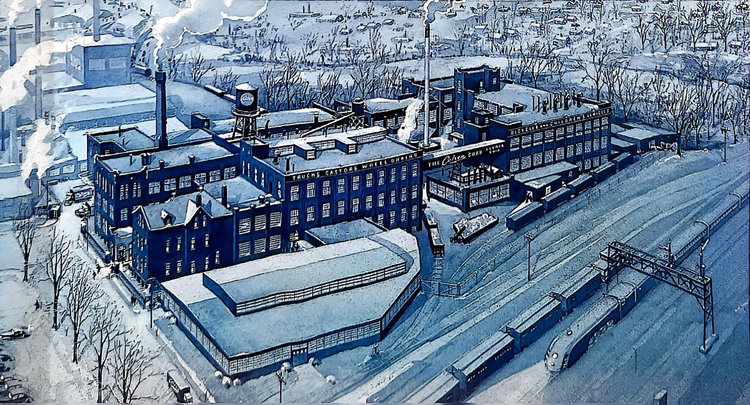

Rockwood & Company was founded in 1886 with initial capital of $14,000 from W.E. Rockwood and W.T. Jones. Over time, the company established itself as a major producer of cocoa and chocolate. By the early 20th century, it was the second-largest chocolate manufacturer in the United States, second only to Hershey’s.

Around that time, chocolate companies began to develop more innovative products. There seems to be a debate over who invented chocolate sprinkles. The Dutch may have been the first to invent them in 1913, but Rockwood & Co. was the first to market them in the U.S. around 1915, selling them as “Decorettes.”

Children may love chocolate sprinkles, but probably not as much as a river of chocolate. In 1919, a fire at Rockwood’s Brooklyn factory led to a literal river of chocolate flooding into the streets. Word traveled quickly, and while the factory was ablaze, children ran in from miles away to drown their faces in chocolate. A newspaper labeled it, “...the greatest little fire that ever occurred in Brooklyn.” A little fire that cost $75,000 ($2M 2025 USD) in damages.

While the children were getting drunk on chocolate, adults were about to be too, thanks to Prohibition.

The federal ban on alcohol led to a large increase in demand for sweets. Rockwood, still one of the three largest chocolate makers, saw its earnings on common shares increase elevenfold, from $2.84 in 1916 to $31 in 1919, with net margins nearly doubling.

Rockwood & Co. entered its second generation of family management when W.T. Jones' son – also named W.T. Jones – took over as president in 1933. This was amidst the worst part of the Great Depression. Since 1929, over a third of U.S. banks had failed, GNP had fallen 31%, and unemployment was almost 25%.

By September 1936, Rockwood & Co. announced a recapitalization plan, swapping accrued dividends on preferred stock for a mixture of cash and new shares, with lower coupon rates attached to the new preferred stock.

More importantly, in 1941, Rockwood & Co. changed its inventory accounting method to LIFO (Last-In, First-Out).

The Accounting

If you’re familiar with accounting, or don’t care to be, you can skip to the break line in this section. For anyone who needs it, here are a few basics1 on inventory accounting.

Imagine you run a business that builds bookshelves. Bookshelves require wood. That wood is called inventory. Over time, the cost to purchase this inventory goes up and down as the market price of wood fluctuates.

In business, we use accrual accounting. That means when you sell a bookshelf for $50, you have to match the sale price with the cost of the specific wood you used for that bookshelf. That matching determines your profit.

But what if you bought wood in January for $10 and more in March for $15? When you sell a bookshelf in April, which cost do you use? Enter the two primary inventory accounting methods: FIFO and LIFO.

FIFO (First-In, First-Out) assumes the first wood you purchased is the first wood you used. Your cost is $10. Your profit on a $50 sale is $40. Pretty basic. The name reflects the logical flow of inventory for most businesses.

During a period of rising prices, FIFO shows higher reported profits and, consequently, a higher tax bill. But it also means your ending inventory (what’s leftover on your balance sheet) reflects the most recent purchase prices, which is usually a better estimate of what the inventory is worth today.

LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) assumes the last wood you purchased is the first wood you used. Your cost is $15. Your profit on a $50 sale is $35. This may not reflect the physical flow of your operations, but it does a better job of matching your most current costs to your current revenue and gives you a more accurate picture of your real profit margins.

During a period of rising prices, LIFO results in a lower reported profit and a lower tax bill. But because the oldest, cheapest inventory remains on your balance sheet, your ending inventory is understated compared to current market values.

Whichever you choose is just a paper election – an assumption for accounting purposes, not a physical requirement. If you sell milk, you will always practice physical FIFO (oldest cartons in front; newest in back). But, you could still choose to use LIFO for accounting and tax purposes.

This is a major point of debate against the use of LIFO. It’s why the Supreme Court in 1930 said it misrepresents the facts, and is why it’s disallowed under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS, as opposed to the U.S. system, GAAP).

However, for a business sensitive to commodity prices – like copper or…cocoa – where the raw material increases substantially, you could find yourself strapped for cash without it. Your tax burden increases on “profits” that don’t really exist because all that money has to go back into replacing inventory at higher prices.

--------------------------------------------------

Prior to 1938, companies were effectively required to use the FIFO (First-In, First-Out) inventory method for tax purposes. A 1930 U.S. Supreme Court ruling had disallowed LIFO-type methods, stating they could obscure the true gain or loss for a tax year and misrepresent the facts.2

The problem with FIFO was that during a period of rising prices, companies had to calculate profits using the cost of their oldest, cheapest inventory. This created large paper inventory profits (profits that appeared on financial statements but didn’t reflect real cash gains). Companies then had to pay a very real cash tax on this phantom profit, even though they needed that cash to buy new, more expensive raw materials just to maintain operations. For a company facing years of increasing prices, this could drain working capital and strain liquidity.

The Revenue Act of 1936 increased corporate tax rates and introduced an additional tax on undistributed profits. Leather manufacturers and metal processors lobbied Congress for relief from taxes on inventory profits, and with the Revenue Act of 1938, were allowed to adopt LIFO (and the tax on undistributed profits was repealed). A year later, the LIFO option was extended to all companies, regardless of the industry.

Fearing a decrease in tax revenue, the government mandated a LIFO conformity rule where if a company uses LIFO for taxes, it must also use it for its financial reports to shareholders. The government expected that companies would choose not to adopt LIFO for tax savings if it meant reporting lower profits to shareholders.

The Setup

However, the onset of World War II created an inflationary environment. In 1941, the wholesale price index rose 11.2%, with further increases expected. With companies facing the highest corporate tax rates to that point (31%) in addition to an excess profits tax, there was a series of LIFO adoptions by corporations, including Rockwood & Co.

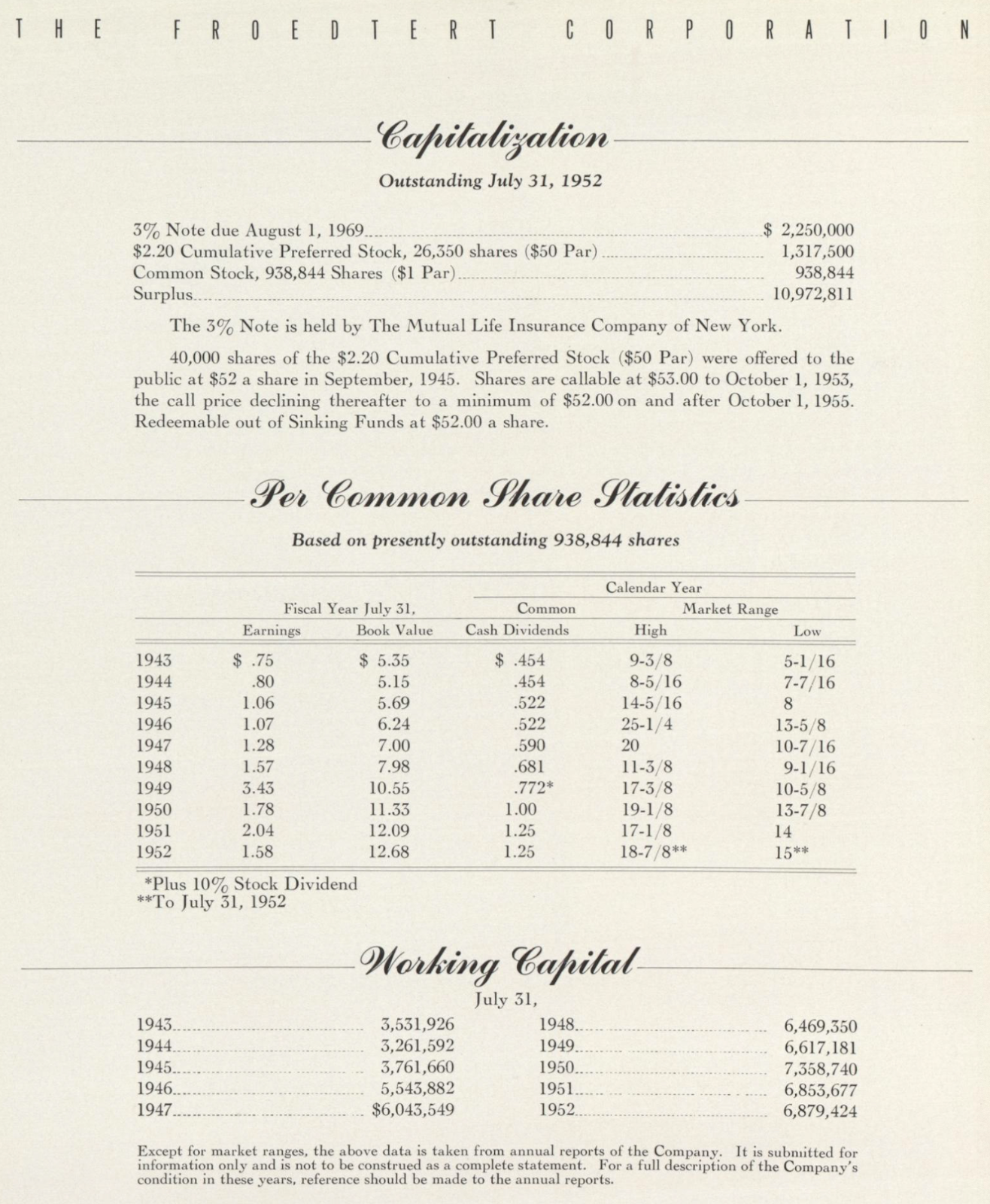

In 1946, Jones passed away, and less than a year later the company was in talks to merge with Froedtert Grain & Malting Company, based in Wisconsin. Froedtert was the largest commercial maltster in the world at the time, which shouldn’t be surprising if you know anything about the per capita consumption of beer in Wisconsin. Even today, the reported world's leading producer of specialty malts – which supplies more than half the country’s craft brewers – is in Wisconsin.

The proposed deal was an all-stock merger, with Rockwood shareholders receiving a mix of common and preferred shares in the new company. For each share of Rockwood stock held, shareholders would get five-eighths of a share of NewCo common stock and one-fifth of a NewCo 4.4% cumulative prior preference share. That preferred stock was temporarily convertible into 3⅛ shares of NewCo common. Froedtert shareholders would receive 1:1 in NewCo stock, and the company would retire its own debt and preferred shares in the process, simplifying its capital structure.

However, certain minority stockholders of Rockwood & Co. disapproved of the merger plan. Neither company wanted to press a deal unless acceptable to all stockholders, so both companies agreed to defer the merger indefinitely.

By now, Rockwood & Co was facing several headwinds. Rockwood's products lacked the brand recognition of Hershey or Nestlé, had little pricing power and was barely profitable. Its Brooklyn plant was old and inefficient, a "textbook case of every problem known to man," as Robert Pritzker would later describe a similar acquisition.

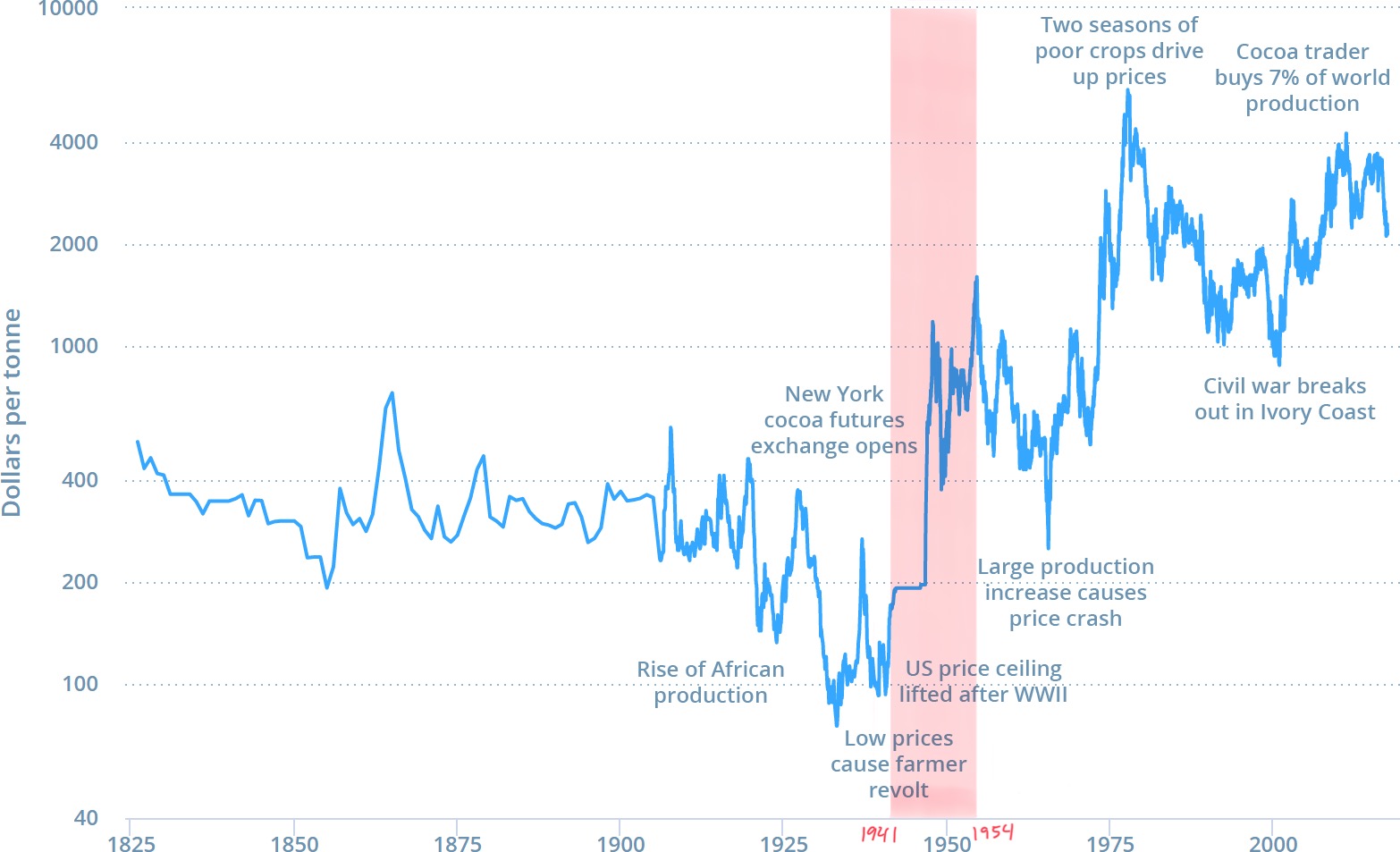

Following World War II, global cocoa prices began to rise, putting Rockwood & Co. in a peculiar position. The company had adopted the LIFO accounting method in 1941. As a result, its 25 million pounds of cocoa inventory remained on the balance sheet at a cost of just five cents per pound. As long as the company maintained that inventory level, the low cost-basis was locked in.

While Rockwood was struggling as an operating business, its shareholders were aware of the company’s “hidden” value and wanted to liquidate.

Rockwood’s market capitalization was ~$2.5M in common stock, ~$2.5M in preferred stock, and ~$300k net debt3 – an enterprise value of less than $6M. Meanwhile, the market value of its cocoa inventory was more than twice that.

However, if Rockwood sold the inventory directly it would have triggered a corporate tax on the profits of nearly 50%. Then, Rockwood would pay a dividend, which is taxed as ordinary income. Depending on your income tax bracket in 1954, that was between 20-91%. Trying to distribute the cocoa directly to shareholders would have also been treated as a dividend.

By 1954, cocoa prices had skyrocketed. So much so that three men were arrested for skimming bags of cocoa beans worth $200k4 ($2.5M 2025 USD) over a nine-month period while delivering truckloads between Rockwood & Co.’s plant and warehouse (for example, stealing 23 bags on a 200-bag truckload).

The Golden Ticket

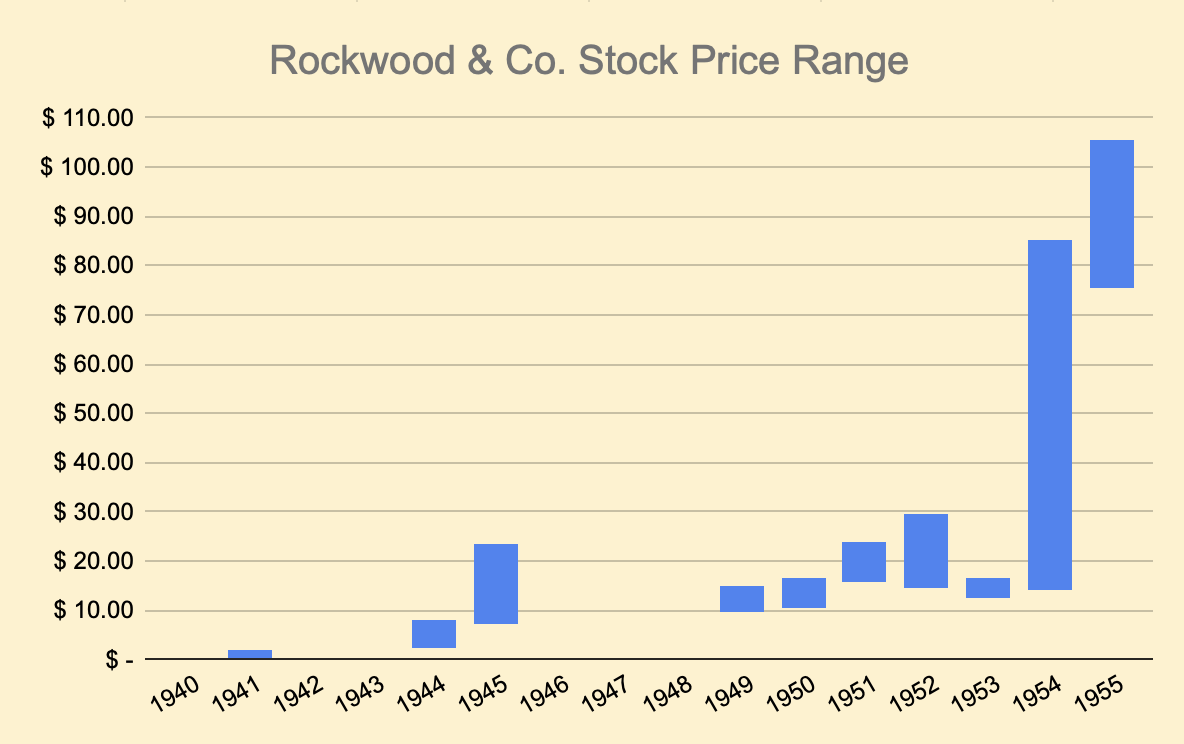

In The Snowball, Alice Schroeder mentions that Rockwood had approached Graham-Newman about acquiring the company, but Graham-Newman didn’t want to pay the asking price. So Rockwood’s president, Russell Burbank, took a meeting with Jay Pritzker.

Jay, then just 32 years old, was meeting Burbank with an idea to merge a different company he was involved with into Rockwood. That company was Colson, and it’s the origin story of The Marmon Group. The hope was to merge Colson with a company that could finance its operations.

Jay quickly realized that Rockwood wasn’t the solution he was looking for, but he did see an opportunity. "Your stockholders are right," Jay said on the logic of liquidating. But Burbank was adamant: "I don't want to liquidate. I want to run the company. I think we can make it work."

This conflict between shareholders wanting to cash out and a president wanting to operate created the perfect opening.

The Law

In 1935, the General Utilities & Operating Co. v. Helvering case established the General Utilities doctrine. This was a U.S. tax rule that allowed corporations to distribute appreciated assets to shareholders without the corporation itself recognizing a taxable gain.

The 1954 Internal Revenue Code (IRC) expanded on this doctrine, which contained the following relevant sections for the Rockwood transaction:

- IRC §336 said a corporation would not recognize a gain or loss when distributing property during a partial or complete liquidation of the business. “Distributing property” implied an internal transaction with shareholders.

- IRC §337 said if a corporation sold or exchanged assets during a complete liquidation, the corporation wouldn’t recognize a gain or loss from that transaction. “Sold or exchanged” implied a transaction with an outside party. However, it did not apply to the sale of inventory.

- IRC §346 said a partial liquidation could avoid corporate-level tax if the distribution was part of a legitimate reduction in the scope of the business and not, “essentially equivalent to a dividend.”

- IRC §331 said any amount distributed (to shareholders) during a partial or complete liquidation is treated as sale or exchange of stock, and so taxed as capital gains, not dividends (ordinary income).

So, Jay Pritzker was about to solve two problems, 1) avoid double taxation by getting around the corporate-level tax altogether, and 2) lower the tax rate shareholders personally faced (20-91%) by qualifying the transaction for capital gains tax (25%).

The key was to structure the transaction as a partial liquidation of the company by reducing the company’s operations.

Jay asked Burbank if any part of Rockwood's business could be discontinued. Burbank confirmed that the production of cocoa butter, a byproduct that was often profitless, could be terminated.

“I have an idea that can solve your problem,” said Jay. “I’ll give it to you if you’ll arrange for us to buy fifteen percent of Rockwood stock that I understand is owned by the Harris Bank.” Burbank agreed after Jay promised they’d try to resuscitate the chocolate operations for at least two years.

Take a moment to appreciate the brilliance here. Plenty of people inside and outside the company knew the value locked up inside Rockwood’s balance sheet. And in walked Jay Pritzker, looking to do a completely different type of deal but intimately familiar with, as Warren Buffett described it, “arcane provisions” inside the U.S. tax code. He abandons one idea, recognizing the opportunity of another.

The Transaction

In September 1954, Rockwood & Co. formally announced the discontinuation of selling cocoa butter. By October, an offer to exchange shares for cocoa beans was in the papers. The company offered to repurchase its stock in exchange for cocoa beans in the following ratios:

- 80lbs of cocoa beans in exchange for each common share

- 190lbs for each preferred share

- 200lbs for each prior preference share

The offer was for up to ~13.5 million pounds of cocoa beans and was set to expire November 10, 1954.

The arbitrage opportunity brought together three of the most iconic investors: Jay Pritzker, Benjamin Graham and Warren Buffett.

Benjamin Graham

Ben Graham is widely considered the father of value investing. He was a teacher and mentor to Warren Buffett, and ran a hedge fund, Graham-Newman.

For Graham, this was a classic arbitrage play. He had Buffett buy Rockwood shares on the open market, exchange them for the warehouse receipts for cocoa beans, and simultaneously sell the cocoa beans forward on the commodity exchange, locking in a nearly risk-free profit.

According to Schroeder, Graham-Newman was buying common shares at $34 and selling the cocoa warehouse certificates at $36, for $2 profit on each share of Rockwood common stock, before the cost of selling cocoa futures to hedge against the price of cocoa falling, which it did.

Warren Buffett

Needing no introduction, Buffett, then twenty-five years old and working for Graham, was tasked with executing these trades. While he did so for the firm, he saw a different opportunity for his own money. Instead of taking the quick arbitrage profit, he decided to hold onto his Rockwood shares, aligning himself with Jay Pritzker.

In February 1955, Buffett wrote a letter stating Jay Pritzker,

has operated quite fast in the past. He bought the Colson Corp. a couple years ago [the company that Jay initially met with Rockwood management about merging into] and after selling the bicycle division to Evans Products sold the balance to F. L. Jacobs. He bought Hiller & Hard about a year ago and immediately discontinued the pork-slaughtering business and changed it into a more or less real estate company.” Pritzker, he writes, “has about half the stock of Rockwood, which represents about $3 million in cocoa value. I am quite sure he is not happy about sitting with this kind of money in inventory of this type and will be looking for a merger of some sort promptly.5

Buffett purchased 222 shares of Rockwood and held them through 1956. Schroeder estimates he earned around $13,000 versus $444 if he’d participated in the arbitrage.

The Pritzkers

Jay paid around $15 per share for his family’s initial ~15% stake in Rockwood in 1954, an investment of approximately $400k (likely financed with borrowed money).

As the market took advantage of the arbitrage, Rockwood’s shares reached a high of $85 for the year. This meant the Pritzkers made 5x their initial investment (unlevered) in a matter of months. Although this was unrealized profit, Jay did receive an offer to sell the entire company, but it meant the company would be liquidated entirely. He kept his word to Burbank and allowed the chocolate division to continue operating for a bit longer instead.

Over the next few years, they purchased the remaining shares on the open market, gaining full control of Rockwood & Co.

The Investment Vehicle

With the cocoa bean arbitrage complete, the Pritzker family’s stake in Rockwood had grown from 15% to over 50% thanks entirely to the share count reduction6, and was worth multiples of their original investment. Jay wasted little time putting Rockwood & Co. to use.

In August 1956, Rockwood & Co. acquired nearly 70% of Selby Shoe Company for around $3 million. Selby Shoe was a Portsmouth, Ohio-based manufacturer of women's and children's shoes. A few months later, Selby was merged into Rockwood. Once merged, they sold the Selby international assets for $1.05M, a factory for $1.25M, and eventually sold the Selby shoe line and trade name.

In April 1957, Rockwood & Co. sold their chocolate division to Sweets Company of America (later known as Tootsie Roll Industries). The result, as Jay Pritzker put it, was that "Rockwood gave us cash and a tax loss and became an investment vehicle."

To review the entire deal, Jay:

- Negotiated a block purchase of 15% of the common shares of a $5.3M EV company (Rockwood) for $400k, likely using borrowed money.

- Used the company’s own assets (the cocoa beans) to buy back enough shares to gain control of over half the company (solving the problem of liquidating the inventory in a tax-efficient manner along the way).

- Sold the rest of the company, keeping the cash from the sale and a shell with a large accumulated tax loss.

- Having turned $400k (or less) of his own money into a tax loss shell containing millions of dollars, he continued to do deals.

For the first time, despite having done many transactions with other companies, Jay had excess cash to reinvest.

In the fall of 1957, Jay used that excess cash inside Rockwood & Co. to purchase another asset: Hyatt House, a single motel near the Los Angeles airport. We’ll get to that another time.

In 1958, the Pritzkers acquired control of James Manufacturing, a producer of farm equipment, and sold the assets to Rockwood & Co. With the James Manufacturing shell still being publicly traded, Jay changed the name to Atkinson Finance Corp and used that shell to purchase 85% of Farm Equipment Acceptance Corp in March 1959.

The Hyatt assets were spun off from Rockwood in the early 60s, and the Rockwood corporate shell continued to be a swiss army knife for Jay. It was used to acquire other companies, like Graham Metal Products, and well into the 1970s, it was used to refinance mortgages on properties owned by the growing Hyatt brand.

Rockwood also played a direct role in building The Marmon Group. In 1971, a regulatory filing showed that Rockwood & Co. owned 9.5% of The Marmon Group.

That year, Rockwood accumulated more than 93% of American Steel and Pump Corporation, transferred the shares into a new Delaware corporation, and acquired the rest of the shares. The divisions became members of The Marmon Group, which was later acquired by Warren Buffett, who described it as a mini-Berkshire Hathaway.

For years, Rockwood continued to operate as a flexible tool, holding interests in everything from manufacturing to timber.

Conclusion

If it feels like I rushed through that last part, that’s because I did. Future articles will look at individual deals and give more attention to histories of the individual companies. For now, I wanted to lay a foundation. To show how interconnected these moves were and how central Rockwood & Co. was for the Pritzker family.

The structure of the Pritzker’s holdings has been described as a dizzying array of trusts, and it’s easy to see why. The web only gets more complicated from here.

Louis Pasteur said, “Chance favors the prepared mind.”

Charlie Munger echoed, “Opportunity comes to the prepared mind.”

Jay Pritzker, whether through photographic memory or many long nights of dull reading, was intimately familiar with the newly enacted 1954 tax code. And, in a pattern we’ll continue to see, he moved at a quick pace.

The 1954 tax code went into effect August 16. One month later, Rockwood had discontinued its cocoa butter operations. On October 4, the cocoa-for-shares swap began. And by the time the exchange offer expired November 10, cocoa prices had already fallen ~15% from the start of the exchange period, and were down ~40% from their August high.

Talk about a confluence of factors.

The Rockwood story is also a lesson about catalysts. Many investors look for situations where a company’s assets are worth far more than the stock price. Rockwood was a textbook example. But everyone knew the value was there. The shareholders knew. Ben Graham likely knew. But it required someone like Jay Pritzker to go in and unlock that value.

It’s frequently debated, but Rockwood shows why value isn’t a catalyst in itself. A safe with $1M inside is worth nothing if you can’t open it. Buying something cheap hoping something good happens isn’t a thesis.

When Warren Buffett said that if he were starting out today he’d be looking at the smallest and most obscure securities, he didn’t mean he’d be passively investing. In the case of Rockwood, Buffett wasn’t betting on the value of the company. He was betting on Jay Pritzker, who had control, as a catalyst.

And being in control makes it a lot easier to answer the three questions necessary to value anything, and with a higher degree of certainty:

- How much cash is there?

- When (how) are you going to get it?

- How sure are you?

The Pritzkers became masters of synergies. In 1988, Jay’s son Tom joked,

You got something that needs a tax loss, I got one of those. You got something that needs a partnership with profits, I got one of those. You need a corporation with losses, yeah, I got one of those too. You name it, we got it!

Most people think of Rockwood as a Buffett cocoa arbitrage story when really, it was a launchpad for the Pritzker story. Rockwood & Co. reflects one of the most creative and important deals Jay Pritzker ever did. He transformed Rockwood from a declining chocolate manufacturer into a corporate swiss army knife. The story brought together three of the most iconic investors and played a continuous role in developing two of the Pritzker family’s most important businesses.

It was a sweet deal that led to a long history of service by a brilliant financier. And it’s why I thought it fitting to name this project Rockwood Notes.

Up Next

Here’s what I’m working on next:

- Two case studies diving into The Selby Shoe Co. and The Colson Corp.

- Some content with David Katunarić and, separately, Karst Research

- Two miscellaneous articles I thought would be interesting

Some of this will be paywalled. That money will go to fund more research.

Thank you to everyone who is already supporting this project.

If you’d like to support it in a small way, you can share this article with others or buy me a coffee here.

If you’d like to support it in a big way, consider becoming a paid subscriber (you can find out more on the about page)!

Sources & Further Reading

- Rockwood & Co. Moody’s Manuals

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sprinkles

- Bravetart by Stella Parks, 2017

- Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971)

- https://www.hyperhistory.com/online_n2/connections_n2/great_depression.html

- Hershey Chocolate Corporate Reports

- The Sweets Company of America Corporate Reports

- The Making of The Marmon Group, Jack Steinberg

- The Froedtert Corporation Corporate Reports

- https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm

- https://www.winton.com/news/cocoas-bittersweet-bounty-200-years-in-charts

- https://emke.uwm.edu/entry/malt-industry/

- https://wisconsinindependent.com/economy/manitowoc-specialty-malt-capital-of-the-world/

- https://www.accountingin.com/accounting-historians-journal/volume-16-number-1/legislative-history-of-the-allowance-of-lifo-for-tax-purposes/

- The Snowball by Alice Schroeder

- https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/296/200/

- 1947-01-24 The Winona Daily News

- https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/whole-ball-of-tax-historical-capital-gains-rates

- https://about.hyatt.com/en/hyatthistory.html

-

This section is for people with little or no prior understanding of accounting. For simplicity, I’m ignoring a more accurate description involving works-in-progress, finished goods etc ↩

-

Lucas v. Structural Steel Co., 281 U.S. 264 (1930) ↩

-

Market cap based on a common stock price of $15. Preferred stock valued at par. Numbers are rough approximations. I did not have a year-end balance sheet of Rockwood & Co. for 1953, so had to compare the 1954 year-end balance sheet (after the cocoa swap) against the 1952 balance sheet. ↩

-

At 54 cents per pound ↩

-

The Snowball, Alice Schroeder ↩

-

Common shares outstanding went from 168,507 before the cocoa exchange to 51,425 and 40,510 at year-end 1954 and 1955, respectively. ↩

© 2025 Rockwood Notes LLC. All rights reserved.

Member discussion