Darling, Fraud & Fortune

The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of Equity Funding Corporation of America

The company Fortune magazine called the fastest-growing diversified financial firm in America was, according to the trustee who later untangled its affairs, "virtually a fiction."

When Equity Funding Corporation of America collapsed in April 1973, auditors found the company had likely never earned a legitimate profit. Executives had invented $2 billion in insurance policies. Two-thirds of one subsidiary's entire book of business did not exist. Eventually, they began "killing" fake policyholders to collect death benefits on people who had never lived.

It became known as "Wall Street's Watergate." Perhaps 100 people knew about it. Twenty-two were convicted.

A federal grand jury later concluded the fraud began in January 1965. If true, the company never issued an honest annual report to public shareholders.

In the aftermath emerged Orion Capital Corp. On the first day of trading in October 1976, Orion shares traded at a split-adjusted price of $1.36. The British insurer Royal & SunAlliance acquired them for $50 in 1999. About 20% compound annual returns including dividends for 23 years.

Part I: The Fraud

The Equity Funding Concept

Gordon McCormick developed the "equity funding" idea in the late 1950s. Customers would buy mutual fund shares, borrow against them to pay life insurance premiums, and hope fund appreciation exceeded interest costs over 10 years. If it worked, the insurance was effectively free.

The idea had great appeal in those roaring bull market days, McCormick later told Forbes. It brought in plenty of commissions. But, he needed a sales force to sell it so he ran an ad in the paper.

"I hired Goldblum like that," McCormick said. "He was a bright guy."

Stanley Goldblum ran a small Los Angeles insurance agency. Before that, he had been a scrap dealer and a meat salesman. In 1959, he and McCormick partnered with Raymond Platt and Eugene Cuthbertson to form Tongor Corporation of America, soon renamed Equity Funding Corporation of America (EFCA).

Two years later, Goldblum and his partners pushed McCormick out, paying him $60,000.

McCormick later alleged the fraud began early. "Even when he was working for me," he told Forbes, "Goldblum would file phony insurance applications to get the agency advance."

The four remaining founders each took a quarter stake. Goldblum became the "inside man" handling administration and finance. Michael Riordan, described as genial, hard-drinking and fun-loving, became the "outside man" building the sales force. Platt and Cuthbertson later left the company, selling their stock.

Platt was a talented salesman with a reputation for drinking. He was removed as an officer in 1962 after he lost $25,000 gambling at Lake Tahoe, another $12,000 at the Tropicana in Las Vegas, and paid bar tabs with company stock. He died at 38 falling off a barstool of a heart attack.

Goldblum didn't hide his views about his former partners. "All but Riordan were just excess baggage I inherited," he told Forbes. "They just didn't have it, and they had to get off a moving train."

McCormick went on to get rich developing insurance ideas for CNA Financial and Waddell & Reed. Later, he bought and flipped small insurance companies and banks.

He had no regrets leaving Equity Funding Corp. "Wondering every day when a Ray Dirks would arrive and we'd all go to jail?" McCormick said. "There's no Rolls-Royce comfortable enough for me to live that life." Dirks was the analyst who would eventually expose the fraud.

Wall Street Darling

EFCA went public in December 1964, selling 100,000 shares at $6 per share.

By early 1973, EFCA shares were trading on the New York Stock Exchange at about $37. The company had managed to produce continued high earnings growth and was a Wall Street darling.

Stock options were the main incentive for the marketing force. As the share price rose — reaching over $80 at its peak — options made early salesmen very wealthy which created euphoric expectations. "Every man a millionaire" became the salesmen's mantra.

This compensation structure incentivized management to keep the stock price up.

We are very bothered if our stock is not selling at a level we feel measures our effort and achievements. It is like getting a zero score for a game well played. – Goldblum

Fraudulent financial statements may have been published as early as 1964.

Riordan died in a January 1969 mudslide at his Los Angeles home. Goldblum became sole chief executive and installed a management team that governed EFCA until the fraud's disclosure.

Samuel Lowell became executive vice president for corporate operations and finance, responsible for accounting. Fred Levin became executive vice president for insurance operations and marketing. Both were directors and reported directly to Goldblum. Both departments operated under direct lines of authority with limited controls.

Goldblum was a 6-foot-4 weight lifter. He had a knack for putdowns that alienated people, yet also acted like a puritan. Some secretaries called him "God."

Lawrence Williams, EFCA's vice president for compliance and a former SEC enforcement officer, later said he was "completely taken in."

"He gave you the impression that if he caught somebody stealing, he wanted him out," Williams said. "He seemed so upright."

But in February 1969, Goldblum told Fred Levin that,

Publicly held companies do not lose money.

Goldblum projected wealth. He had a maroon Rolls-Royce and a Ferrari at his Beverly Hills home garage. His corner office on the top floor of 1900 Avenue of the Stars in Los Angeles featured a gilt-edged leather desk kept entirely bare except for a fancy inkwell. He kept his telephone in a drawer to maintain the aesthetic.

Goldblum's compensation equaled $304,000 plus $36,000 for entertainment.

Levin was different – charismatic. He told a friend his greatest asset was an ability to "mesmerize" people.

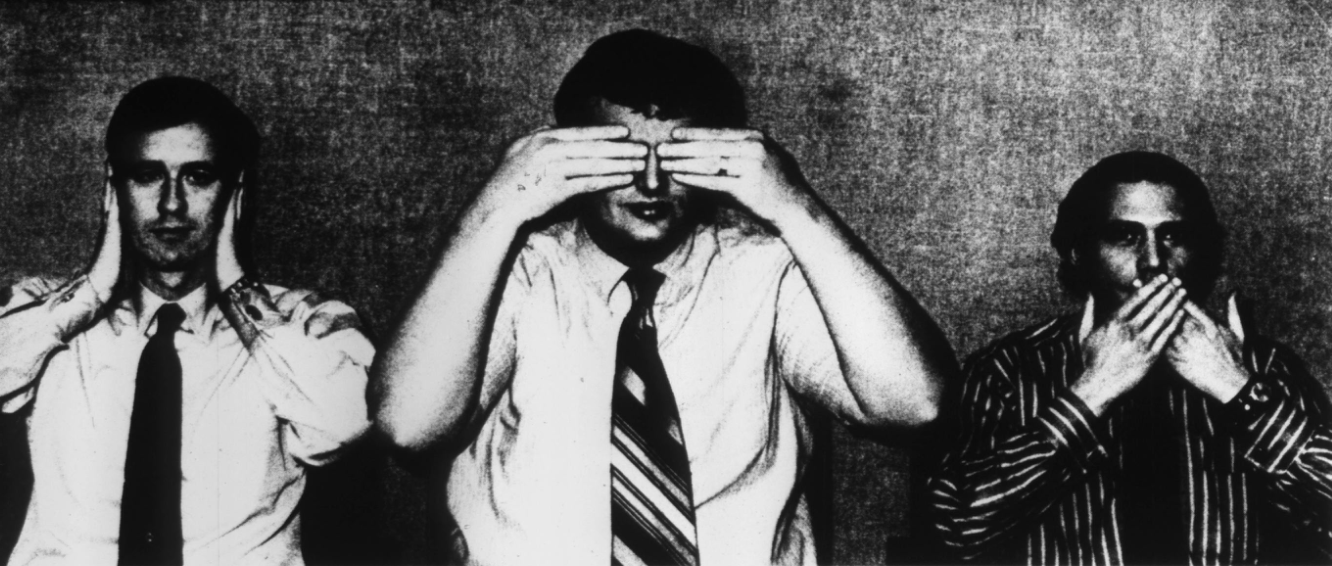

He brought in three young men who would assume key roles in the fraud: Jim Smith as vice president and chief administrator of the insurance subsidiaries, Lloyd Edens as vice president for financial services, and Arthur Lewis as chief actuary.

Lewis controlled a separate IBM System 3 computer used to track the underlying realities as the frauds grew larger.

Equity Funding may have set a record for compensation of executives under 40. Levin (mid-thirties) earned $249,000 in salary and stock bonuses. Smith (mid-thirties) got $118,000. Edens and Lewis (mid-twenties) each received $83,000.

At one point, the three posed for a gag photo — Smith covering his ears, Edens covering his eyes, Lewis covering his mouth. Hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil.

They were preparing the company's fraudulent financial statements at the time.

In 1967, EFCA bought Presidential Life Insurance Company of America for $6 million, renaming it Equity Funding Life Insurance Company (EFLIC). Crown Savings and Loan followed in 1968 for $5.3 million.

In 1969 came Investors Planning Corporation for $10.2 million, Ankony Farms cattle operations for $12.5 million, and Bishops Bank and Trust Company for $578,800.

Bankers National Life Insurance Company cost $62.8 million in stock in 1971. Northern Life Insurance Company cost $31.2 million cash plus $8 million in notes in 1972.

By early 1973, EFCA's annual report was at the printer. It showed a company with consolidated assets approaching three-quarters of a billion dollars, net earnings exceeding $22 million, stockholders' equity over $143 million, and more than 4,000 salesmen operating from over 100 branch offices.

The stock market valued the company at over a quarter billion dollars.

Four years earlier, Forbes had profiled Goldblum and closed with a warning:

That's the thing about the Stanley Goldblums of this world: They refuse to believe that luck plays a major part in their success. They tend to attribute it all to their own brains and energy. Which is why they move ahead so fast. And which is why they sometimes fall on their faces when things start going wrong. Frankly we don't know how the Goldblum saga is going to end, but we do know that Goldblum can't stop with what he's got now.

Three Types of Fraud

There were three fraudulent practices designed to inflate earnings and assets and maintain the illusion of growth.

The first involved inflating assets. The largest distortions were periodic fraudulent increases in customer loan balances. As this account was inflated, corresponding fake commission earnings were booked.

Initially the increases came in single year-end increments. By 1972, fraudulent increases of $2 million were booked every month.

The second involved unrecorded borrowings. Cash from certain loans was never recorded as debt. This cash was called a "free credit" and used to inflate earnings or reduce a fake asset account. The illegitimate uses were supported by fraudulent accounting entries, fake companies and fictitious transactions.

The third involved made-up insurance policies. This began as a duct tape workaround. After acquiring EFLIC in 1967, EFCA had a commitment to place $250 million in policies with Pennsylvania Life but wanted to push its own EFLIC products instead.

To meet its commitment, EFCA came up with "special class" insurance — EFLIC policies with small premiums issued to employees and families, then reinsured with Penn.

When employees let policies expire rather than pay renewal premiums, EFCA itself made payments to Penn to reduce the apparent lapse rate.

Before long, EFLIC was "selling" policies to reinsurers, receiving 180 to 190 percent of first-year premiums upfront. The upfront payment was an advance against future premiums EFLIC would collect and pass through. For fake policies, EFLIC pocketed the cash but there were no future premiums coming in — so it had to pay the reinsurer out of pocket year after year. The reinsurer never dealt directly with policyholders; they just received checks from EFLIC. That's why they were none the wiser.

It resembled a pyramid scheme. A company that regularly reinsures must sell increasing amounts each year to show growth because it cannot build on revenues from past policies. EFLIC had to dramatically increase real sales or create even more fake policies. Guess which they opted for.

The end result was the size of manipulations had to increase exponentially. Another term for that is 'unsustainable.'

Of the $2.2 billion in life insurance shown in force at December 31, 1971, about $1.3 billion (59%) was not real. A year later, of the $3.2 billion shown in force, about $2.1 billion (66%) was fictitious.

Employees coded fake policies as "Class 99" in the computer system, meaning business that involved no direct billing. By the collapse, between 56,000 and 64,000 fake policies existed — approximately two-thirds of EFLIC's total book.

Eventually, they began killing off the fake policyholders to collect death benefits — real money paid out on people who had never existed.

The first documented death claim came on May 19, 1971, when corporate counsel James Banks mailed forged documents to Phoenix Mutual Life Insurance Company claiming the death of "Fenton Taylor, insured under fictitious EFLIC policy number 7101481."

The Insurance Factory

To hide the fake insurance policies, EFLIC had to create all the corresponding paperwork – booking reserves, recording costs, even paying state taxes on premiums that didn't exist. Expenses were falsified so the ratios between income and costs looked normal to auditors.

In a small building a couple of miles from headquarters, Arthur Lewis's younger brother ran Equity Funding's "mass-marketing office." It was staffed by young women who apparently didn't fully comprehend what they were doing: creating fake policy files to match the fake policies in the computer.

"On a very good day we could manufacture between fifteen and twenty policies," Mark Lewis later said. "It was like an assembly line."

The building had no windows, the air conditioning constantly broke down and the roof leaked. To boost morale, the staff held parties after each policy-manufacturing project. They'd celebrate with champagne; sometimes get drunk. In between projects some women knitted blankets. They had come nowhere near completing the task when the fraud hit the news.

To trick auditors about $24.6 million in bonds supposedly held at American National Bank & Trust Co. of Chicago, Levin rented an office in Highland Park, Illinois, and named it American National Trust Co. — yes, deliberately similar to the bank's name.

When auditors Seidman & Seidman mailed confirmation requests, they went to Highland Park instead of the bank. An imaginary "Joseph S. Phillips, second vice president" signed and returned them.

The court trustee's later report detailed it:

From time to time thereafter, fraud participants sent letters addressed to 'American National Bank' at the mail drop address to accustom post office employees to delivering mail so addressed to the bogus location.

An EFCA officer went to Chicago to receive the auditors' confirmation request at the phony branch. For several days nothing arrived, "causing great consternation among the conspirators who feared that the post office had delivered the request to the real American National Bank and Trust Co."

They later learned the auditors had forgotten to mail it. When it finally arrived at the mail drop, an officer signed and returned it to Los Angeles.

A careful auditor might have noticed the suburban address did not match the downtown bank. They did not.

For funded loans, company employees used the computer to prepare a detailed trial balance listing all individual loans — but the listing omitted borrowers' names and the first two digits of each five-digit loan number. They balanced it by listing legitimate loans multiple times until reaching the desired fictitious total.

When auditors selected duplicate loans for testing, company personnel either produced documentation for other loans with matching balances and similar numbers, or created counterfeit documentation.

When auditors selected 2,000 funding programs to verify with customers, someone took the sample from the computer, identified which accounts were duplicates, and replaced them with real names and addresses.

Some came from friends persuaded to return confirmations. According to Fortune, some names were taken from the invitation list for Arthur Lewis's wedding.

When auditors tried to verify policies by writing to salesmen at branch offices, 66 letters went out. Equity Funding told the branches the requests were sent by mistake and should simply be confirmed. Forty-nine came back with positive confirmations.

For those that came back negative, EFLIC made a plan to have coworkers pretend to be salesmen around the country and "confirm" policies over a speaker telephone in the presence of accountants.

Fred Levin had forbidden auditors to mail confirmations directly to policyholders, claiming it would "upset the salesmen."

Complicity

The fraud was not a sophisticated computer operation run by a few people, as was first suspected.

Instead, a large number of employees had pitched in to develop and maintain a false image of growth and prosperity. Some accounts compared the revelations of EFCA to a "white-collar Mylai" — referring to the Vietnam War massacre that changed assumptions about American conduct.

With so many people aware of the fraud, why didn't anybody tell?

The court-appointed trustee believed 50 to 75 employees knew or suspected something was wrong. Ray Dirks, the analyst who exposed the fraud, speculated that 100 "seems like a reasonable guess."

Twenty-two men were ultimately convicted and four others were acknowledged coconspirators.

Motives varied. The inner circle — Goldblum, Levin, Lowell, Smith, Lewis — received big salaries, stock options and aesthetically pleasing offices. Others weren't getting rich and treated it almost like a game.

The trustee's report noted some participants' "curious flippancy" and said that some of them "appeared to have looked upon the fraud as a game."

The inner circle was also young. Except for Goldblum, who was 46, none of the 10 men forced out of the company was older than 35.

But for some, the fraud was agonizing. Bill Symonds, a middle-level manager who later pleaded guilty to securities fraud, was reportedly consumed by it. Someone who watched Symonds closely remembered: "It preyed on his mind, like a death wish. He wanted the whole thing to collapse, it bothered him so much."

Others rationalized their way in gradually.

A computer programmer said: "Like wow! I was kind of wondering what to do about it. I was told that this was a short-lived financing to acquire Bankers and Northern."

Under constant pressure from Art Lewis and others, the programmer tried to keep his distance by doing less than they asked. It wasn't long before he became deeply involved.

When the fraud burst, he was at work on a computer program to take over the task of "killing off" selected policyholders of the phony policies. He developed pride in this work. The trick, he explained, was to kill off as many of the fictitious policyholders as possible without producing a pattern of "deaths" that would raise the reinsurers' suspicions.

Gary Beckerman, a young advertising specialist convicted of fraud, rationalized the "special class" insurance: "I asked myself, 'Is it honorable?' No. 'Who's hurt?' The reinsurers. 'Is the reinsurer a big boy?' You bet."

By 1972, suspicions were spreading. Several executives at Bankers National questioned the accounting and quit. One investment vice president resigned after only three months, refusing a big raise from Levin. He remembered Levin attempting to appeal to his integrity. "If I had met you before we started this, maybe I wouldn't have done it," Levin told him. "But now we're trapped."

At Bankers National in New Jersey, four transferred employees who discovered the fraud decided to make a promise. Pat Hopper, vice president for investments; Ron Secrist, vice president for administration; Rick Stevens, head of computer operations; and Tom Patterson, head of personnel, vowed that Equity Funding was not going to do anything to Bankers. They would resist any attempt to spread the fraud to the subsidiary. None went to authorities. Dirks later reflected on why.

Not one of the people whose witness enabled me to expose the fraud had been willing to go to the authorities," he wrote. "They were afraid the authorities might do nothing. They were afraid they wouldn't be believed. They were afraid the authorities would take their information back to the company — thereby exposing them. They were afraid their careers would suffer and that they might expose themselves to physical harm. They were afraid, at the very least, that they would carry the taint of 'informer.'

Discovery and Collapse

Ronald Secrist, a 38-year-old vice president fired in February 1973 following a disagreement over a Christmas bonus, made two phone calls on March 6.

One went to Raymond Dirks, a securities analyst at Delafield Childs Inc. who specialized in insurance. The other went to the New York State Department of Insurance.

Secrist claimed EFLIC had created more than $2 billion in nonexistent policies reinsured with other companies. Dirks investigated immediately.

On March 12, EFCA publicly reported 1972 earnings of over $22 million — a 17% increase. That same day, the Illinois Insurance Department began an audit at EFLIC pretending it was a routine examination.

Dirks flew to Los Angeles on March 19 and met with former EFLIC employees who confirmed many of Secrist's charges. On March 21, he met with Goldblum and Levin and told them his concerns.

By the end of the week, Dirks had met with Seidman & Seidman and Haskins & Sells, providing copies of his notes. On March 26, Dirks met with the SEC. Goldblum met with the auditors and said he was unaware of irregularities.

But word spread and institutional investors began selling large blocks causing the price to decline.

On March 27, Goldblum issued a press release calling the rumors untrue and announcing plans to purchase 1 million EFCA shares. The New York Stock Exchange halted trading.

On March 28, the SEC suspended trading in all EFCA securities. Three months earlier, the stock had traded at $37. By now it had fallen to $14.

Illinois auditors discovered millions of dollars in bonds that should have been held by EFLIC were missing and had never been in the reported depository bank.

On Friday, March 30, the California Insurance Department took control of EFLIC. Larry Baker, the department's second-in-command, went into EFLIC's offices throwing seizure orders on everyone in sight. But he was less confident than he projected.

"At that point we had not found one fake policy," he later admitted. "We had nothing but stories. Our hearts were in our mouths."

April Fools...?

On April 1, 1973, EFCA's board of directors gathered for what Fortune called "one of the more memorable business meetings of 1973."

All nine directors attended, along with seven lawyers.

They did not meet in EFCA's fancy boardroom on the top floor of 1900 Avenue of the Stars. Instead, they met 18 floors lower, in a nondescript conference room at bankruptcy specialists Buchalter, Nemer, Fields & Savitch.

There was a reason. A cleaning woman had discovered a tape recorder in Goldblum's private bathroom, with a cord going into the ceiling toward the adjacent boardroom. Federal investigators later found the bugging equipment had been pulled out of the floor where Illinois insurance examiners were working, but wires and microphones were still in the walls.

Since it was Sunday, the building's air conditioning was off. The conference room filled with cigarette smoke and the smell of half-eaten pastrami sandwiches.

Goldblum, seated at the head of the table, tried to take charge — questioning the presence of outside lawyers and suggesting the meeting had been improperly called.

Director Gale Livingston, a Litton Industries executive who had known Goldblum since 1962, at first was skeptical that the rumors were true. Thinking he could end the meeting, he turned to Goldblum and asked directly:

Stanley, I want to know one thing. Did you put your fingers in the till? If you answer no, I'll leave right now.

Goldblum replied that he would not answer on the advice of counsel.

Livingston later said he felt "as though the earth would open and swallow me."

Goldblum had the opportunity to do the funniest thing ever and yell April Fools. Except it wasn't a joke.

Everyone started speaking at once, with many swear words sent in Goldblum's direction.

Harvard professor Robert Bowie, who had canceled a speech in Brussels and flown to Los Angeles for the meeting, took over. He told Goldblum that if he, Levin and Lowell would not agree to testify before the SEC, they needed to resign.

Goldblum tried to argue that the company could not be run without them, but Bowie stood firm.

Goldblum asked what the directors had in mind for vacation and severance pay. Bowie found the patience to say it wasn't negotiable.

Finally, Goldblum offered to resign. Levin and Lowell agreed they had to go too — but Levin calmly offered his services to help sort things out, mentioning he had already begun scheduling discussions with two large companies that could give Equity Funding help. The offer was met with awkward silence.

That evening, a banker who had loaned Equity Funding $50 million reached Levin by phone and asked,

"Fred, why did you do it?"

"Jollies," Levin replied. (JOLLIES!?)

"How long has it been going on?"

"It was going on when I got here," Levin said. "I fine-tuned it. It was brilliant."

After the three stepped down, accountants from Seidman & Seidman reported findings from a telephone survey of policyholders. Of 35 people they had reached, only six confirmed they had the policies they were supposed to have.

On April 2, William Blundell's front-page Wall Street Journal story broke the news to the public.

On April 3, banks offset $10 million in EFCA deposits.

On April 4, Rodney Loeb, the general counsel who apparently never suspected the fraud, helped draft the bankruptcy petition. Then he reportedly went home, sat on the edge of his bed, and wept.

On April 5, EFCA filed for bankruptcy — the second-largest such proceeding in American history and the largest computer fraud.

Jerry Nemer, a bankruptcy attorney with 37 years of experience, was stunned by the speed of the collapse.

I have never seen an insolvency — a collapse of a firm in a shorter space of time and with more dramatic impact," he told the court. "On Monday, March 26, this was a vital, vibrant, operating company controlling seven to eight hundred millions. The following Monday, one week later, it was like a bleeding animal on the ground, which was literally dying because its blood was seeping out of it.

Financials

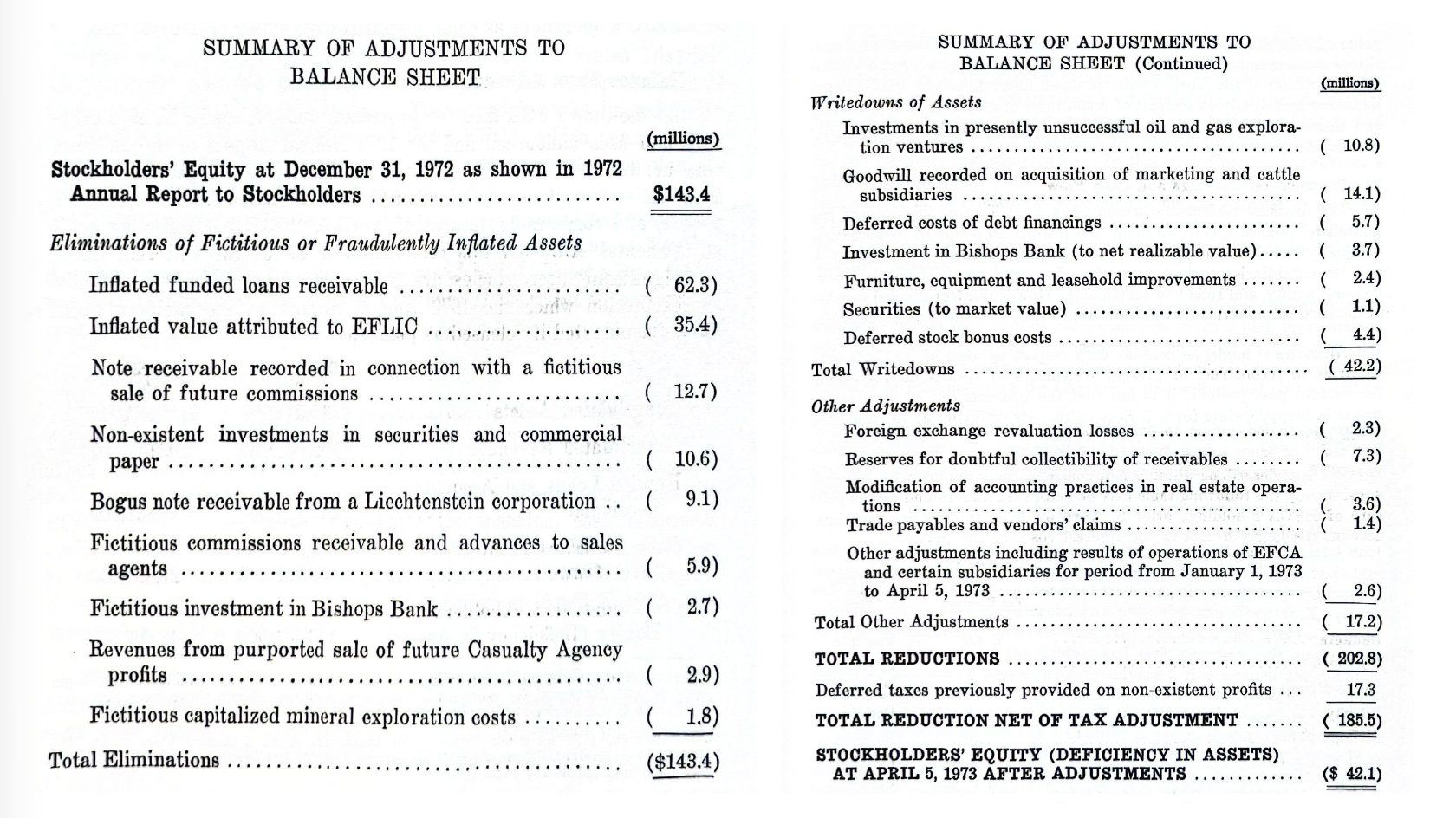

Touche Ross & Co., brought in by the trustee, audited the balance sheet as of April 5, 1973. At one point they had 70 accountants working on Equity Funding. Their fees exceeded $2 million. What they found was not good.

The company that claimed nearly $750 million in consolidated assets actually had $489 million. At the parent level, over 60% of reported cash and short-term investments did not exist, and $117.7 million in reported funded loans receivable turned out to only be $44.8 million. At EFLIC, about 80% of the subsidiary’s assets were nonexistent. Seventy-five percent of the revenue from reinsurance deals came from fake policies.

The trustee concluded,

The company presented to the public and financial community as Equity Funding Corporation of America prior to April 1973 was virtually a fiction concocted by certain members of EFCA's management...it did not have the assets; it did not have the revenues; it did not have the sales; it did not have the net worth; and it had not made the profits.

Aftermath

Twenty-two people were indicted on 105 counts including securities fraud, mail fraud and interstate transportation of counterfeit securities.

In an interview before his trial, Goldblum recited Macbeth to a reporter:

Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player, that struts and frets his hour upon the stage, and then is heard no more: it is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

On October 8, 1974, Goldblum stopped his trial to plead guilty. He received eight years, served four, and paid a $20,000 fine. Levin received seven years. Lowell received five years. Three auditors from Wolfson, Weiner, Ratoff & Lapin were convicted and sentenced to two years each.

In early 1977, settlements were announced that would pay approximately $60 million to former shareholders. Thirty-nine million came from accounting firms.

Other settlements included:

- $5 million from Pennsylvania Life Co., which allegedly discovered the fraudulent practices and extorted EFCA for money to keep quiet.

- $3.5 million from Bache Halsey Stuart Inc. and New York Securities Co., the underwriters of Equity Funding's public offerings.

- $3.45 million from Joseph Froggatt & Co., the auditors of Bankers National Life.

- $3 million from Milliman and Robertson Inc., the actuarial firm that allegedly received finder's fees for helping Equity Funding sell fake insurance policies to other insurance companies.

- $2 million from the estate of Michael Riordan.

Various former officers and directors filed settlements totaling $17,381, plus assignments of their Orion Capital shares. Gale Livingston — the director who had asked Goldblum if he had his fingers in the till — paid $10,000.

The total settlement equaled 15 to 20 cents on the dollar for most investors.

Fortune reported that after his downfall, Fred Levin got a job selling cars under an assumed name. He told friends he was making more money than he had at Equity Funding.

"It is possible, of course, that he is exaggerating — he tends to do that," Fortune reported. "But one thing is certain: whatever he is making is worth a lot more than all the Equity Funding stock bonuses he ever got."

Part II: Reorganization

Complete Anarchy

Robert M. Loeffler, senior vice president and general counsel of Investors Diversified Services in Minneapolis, was appointed trustee five days after the bankruptcy filing.

Judge Harry Pregerson said he was looking for a man with "physical stamina and mental toughness" to take on "the Herculean task of holding this tottering structure together."

Neither Pregerson nor Loeffler had handled a corporate restructuring before. Pregerson didn't want the first one to result in liquidation.

"I said to myself, 'What do you need this grief for?'" Loeffler later remembered. "And as soon as that crossed my mind I said, 'Hold on, Loeffler. If you're in that much of a rut at 50, you need this job.'"

He quit IDS and arrived at Equity Funding on April 11 to find "complete anarchy."

There were no top executives to help because they had all been fired. The few remaining middle-managers were still suspect. Loeffler remembered someone bringing a man into his office and saying, "He's new. He's clean. You can use him."

Bank creditors with $50 million in loans seized Equity Funding deposits held by them. Company paychecks couldn't be cashed because banks didn't want to honor paper signed by Stanley Goldblum.

New Jersey insurance regulators took over the healthy Bankers National subsidiary and wouldn't let go. "Back there, they thought that I was Goldblum's alter ego and that Judge Pregerson was some slick L.A. lawyer," Loeffler said.

With help from lawyers at O'Melveny & Myers, Loeffler found a Texas bank with $1 million of Equity Funding deposited and no loans outstanding to the company. He had a small source of liquidity.

To fix the bouncing checks, he sent a courier on an emergency flight to the Midwest. That's where the plant that provided signatures for Equity Funding's check-writing machine was. They needed to get a new slug made with Loeffler's name on it.

The data processing center was closed and under armed guard while investigators worked. Loeffler's lawyers and accountants advised him to go through the formal process of seeking court permission to open it and then putting an independent service in charge.

"Nobody wanted the responsibility," Loeffler said.

Deciding that this would take too long, he opened it on his own authority and put a data-processing manager in charge he knew had had a peripheral and reluctant role in the fraud. But there was no one else.

"Screw up," the trustee told the manager, "and you're going to wind up on the bottom of the ocean."

Salvaging EFLIC

Equity Funding Life was no better.

The reinsurers who had bought the fake business were demanding restitution. Real policyholders (about 30,000 of them) were overwhelming EFLIC with calls and letters.

The Illinois Insurance Department, which had regulatory authority (EFLIC was chartered in Illinois), named a special deputy to run EFLIC. He was J. Carl Osborne, a 57-year-old semiretired insurance executive.

When he first got to EFLIC, Osborne said,

Boys, if we can hang on to 30% of the real business we've got now, I'm going on a six-week drunk.

They saved about 60% of it. Not one policyholder suffered a loss of equity in their policy. All were eventually transferred to Northern Life with their rights intact.

At the parent company, Loeffler was projecting calm optimism about reorganization. Judge Pregerson told creditors that he was presiding not over the funeral but over the rebirth of Equity Funding.

This air of confident determination is psychologically important in bankruptcy proceedings, experts said. If the people running the company seem at all doubtful, creditors assume the worst, dig in, and fight for every penny rather than compromise.

Loeffler remained confident publicly even after the Touche Ross fraud audit revealed that Equity Funding, which claimed a net worth of $143 million, actually had liabilities outweighing assets by $42 million.

"When we found out what the company's true condition was, the outlook was really pretty bleak," said Gerald Boltz, Western regional chief of the SEC.

Sound Subsidiaries

Unsurprisingly, rumors spread that the fraud extended to every subsidiary — that cattle in Ankony's breeding operation were "computerbred" and did not exist.

Touche Ross conducted a physical field inventory of more than 75,000 cattle. The herds were real and in good condition. Less-so one Touche Ross auditor who fell off his horse during the audit.

Loeffler found subsidiaries with true value.

Bankers National Life, Northern Life, Liberty Savings and Loan, Bishops Bank and Ankony cattle operations had all been operating at a profit. The real estate operations were about breakeven.

EFCA's home office insurance operations, marketing operations and parent company funding business had generated huge losses for years.

Loeffler said,

For the company that EFCA actually was, as contrasted with the company it purported to be, the debt structure it had was impossible to carry. EFCA had interest income on approximately $45 million of funded loans receivable and interest expense on almost $205 million of debt.

Loeffler decided to build the new company around the two sound insurance subsidiaries — Bankers National and Northern Life — and sell almost everything else.

In 1974, he began negotiating with creditors, a process that took one year.

Wearing Everybody Down

An ordinary bankruptcy case proceeds by the rule of absolute priority, which defines creditors and their rank in settlement of claims. Under the rule, no creditor in a given class can get anything until all creditors in the class above have been made whole. Shareholders are at the bottom of the ladder and usually get nothing.

However, EFCA shareholders (along with everyone else) had been completely defrauded by the company. So, practically everybody involved had equally valid legal claims for a piece of the settlement.

Loeffler decided to negotiate a plan that would give something to everybody but still follow the general precedent of priority — secured creditors would get more, and stockholders, less.

"We went to New York one day and had about six meetings with creditor groups," said A. Robert Pisano of O'Melveny & Myers, a principal aide to the trustee. "Everybody told Bob he was nuts and they'd never buy it. When we got back to the hotel at night I laughed and said, 'Well, do we throw in the sponge?'"

Loeffler finally wore everybody down.

"Bob has the capacity to just sit there and take all sorts of guff," Pisano said. "Then he begins to talk; he gives all the legal arguments for the other creditor groups; he gives them ad nauseam. Finally the people he's talking to get convinced or just worn out."

The primary secured creditors — a four-member bank group headed by First National City Bank of New York — were first. Finally convinced that the new company would have a future, they agreed to waive $15 million interest and fees owed to them on $50 million of debt if they could recover the principal. The rest of the debt would be dealt with by issuing them notes in the new company.

Shareholders were not happy with an offer of new stock that would have given them about six cents per dollar of claimed loss.

"The trustee's position was, in effect, that six cents was better than nothing and that if we litigated, nothing might be what we'd finish with," said Marshall Grossman, lead attorney for the stockholder group. "Our position was that six cents was so close to nothing that we might as well litigate anyway."

So, they did.

In April 1975, Judge Pregerson issued an order forcing all such actions into his bankruptcy proceeding. This key ruling helped pave the way for a final settlement with the stockholders, who would get stock in the new company worth an average of 12 cents per dollar of loss claimed.

Finally, everyone was in line. Creditors approved the plan in February 1976.

In total, 7,851,137 shares of Orion stock were distributed to former EFCA creditors and stockholders.

Close to Remarkable

The reorganization plan was approved in January 1976. Loeffler put together the reorganization in about three years. The average bankruptcy took seven. Some took ten.

"Some of the problems seemed absolutely insuperable," said a New York bankruptcy lawyer familiar with the case. "Getting a good reorganization was a real achievement; getting it in three years is close to remarkable."

Senator Walter Mondale entered a tribute into the Congressional Record.

"Today marks the culmination of a virtual miracle which has been performed in American business," Mondale said. "I speak of the remarkable effort of a distinguished Minnesotan, Robert Loeffler, in successfully completing the Chapter 10 proceeding in the Equity Funding case."

For three years, Loeffler had been living alone in a Los Angeles hotel room — and later an apartment — only seeing his wife and family on occasional weekends.

Judge Pregerson authorized payment of $10.2 million to attorneys and others involved in the bankruptcy. The largest fee — $5.8 million — was awarded to O'Melveny & Myers. Loeffler was authorized fees of $1 million.

Part III: Post-Bankruptcy

Orion Capital Corporation

Orion Capital Corp. emerged in March 1976 with $30 million in bank debt and a net operating loss carryforward of $85 million.

The federal court appointed Alan R. Gruber as chief executive. Gruber had been director of corporate planning at Xerox and vice president at Heublein. He would lead Orion for 20 years.

His first order of business was a new name. "Phoenix" seemed perfect — rising from the ashes — but it was taken. So, he settled for Orion, the hunter of Greek mythology.

Over-the-counter trading began on Oct. 18, 1976, at a split-adjusted price of $1.36.

The stock immediately attracted value investors like Martin J. Whitman, a 52-year-old who ran his own brokerage firm, taught finance at Yale and later founded Third Avenue Value Fund.

Whitman bought shares at a split-adjusted price of about $1.76. He later invited Gruber to lecture his Yale students on managing a company through bankruptcy.

In his 1979 book "The Aggressive Conservative Investor," Whitman wrote that Orion "upon emergence from bankruptcy, appeared to be a prime takeover candidate."

Management owned less than 1% of shares outstanding. The stock traded below book value. With only 24.5 shares, buying the company "has never been a terribly expensive proposition."

The Pritzker Investment

One of the largest recipients of Orion shares in the bankruptcy distribution was Fidelity Corp., which received about 2.2 million shares, or 9% of shares outstanding. Fidelity had been trying to sell its block without success.

But, in late February 1977, they found a buyer: Jay Pritzker.

This was in the year following their takeover of Cerro Corp., which they merged with Marmon Group.

Pritzker paid about $1.92 per share for the Fidelity block – about $4.3 million.

Jay told the Wall Street Journal,

I thought this was a reasonable investment. We had some cash and thought maybe someone would come along after a while and want to buy them from us.

Defending Independence

The Pritzker purchase came amid the first wave of takeover interest.

Shearson had bought about 1.6 million shares and was pursuing a merger. Sanford Weill, Shearson's chairman, met with the Pritzkers and Orion management to discuss a combination but Gruber rejected the approach.

"Shearson would represent an unduly speculative investment," he wrote to stockholders, noting that Shearson had one of the lowest equity to assets ratios among publicly traded brokerage firms.

The takeover bids did not materialize. Gruber kept a M&A firm on a $40,000 annual retainer, ready to use what Fortune called their "scorched-earth defensive tactics."

More importantly, Gruber had convinced the IRS that his team represented a continuation of Equity Funding's management, allowing Orion to use the tax-loss carryforwards. But, an unfriendly takeover by different management could jeopardize those benefits — its own sort of poison pill.

Charter Co. and U.S. Life expressed interest in subsidiaries but Gruber turned them all down.

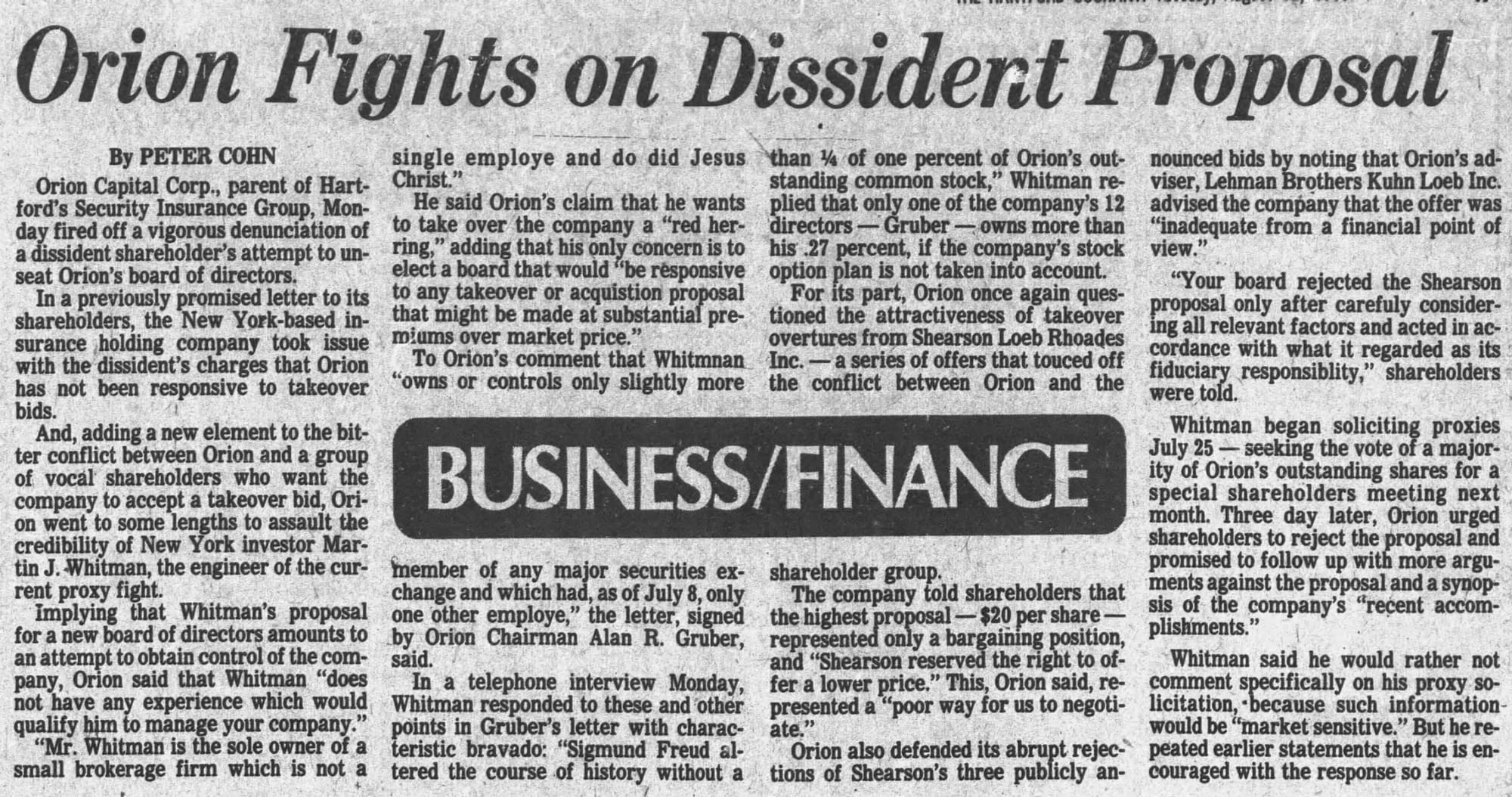

The 1980 Proxy Fight

In April 1980, three Orion stockholders ran a full-page ad in the Wall Street Journal.

The ad mentioned that the market price — about $3.04 — did not reflect true value and advocated for management to solicit takeover bids, not reject them.

Orion's attorneys threatened to sue, claiming the ad was an illegal proxy solicitation, and the group folded. But blood was in the water.

Shearson bought 1.1 million more shares, and Sandy Weill requested a meeting with Gruber.

On May 15, the two men dined at an Upper Manhattan restaurant "unlikely to be graced by many of their acquaintances."

Weill offered $5.12. Gruber called it "ridiculous."

Weill came back at $5.60. Orion rejected it as "grossly inadequate," saying that Weill had offered to improve the "life-style" of top executives with high pay and job security if they supported the takeover.

Weill raised to $6.40 — about double the pre-bid market price.

The board rejected that too.

Martin Whitman, who had kept quiet assuming the refusals were negotiating tactics, called Gruber.

"I told him that he had to sit down with Shearson and negotiate in good faith," Whitman later told Fortune. "He said to me, 'Are you telling me I have to accept?' I said, 'No, but you do have to talk to them.'"

The board rejected the Shearson offer anyway.

Whitman was not happy. He saw the rejection as proof that Gruber was protecting his $200,000 salary ad Mercedes 300D rather than serving shareholders.

Whitman launched a proxy fight to replace the entire board.

"Basically, I am in this fight for the money, not the social justice," he told Fortune.

Gruber responded, "It's insulting to the board to suggest that it is more interested in my career than in the interests of the stockholders."

Whitman gathered support from arbitrage funds and individual investors but gained little ground with banks like J.P. Morgan and BancOhio that had gotten Orion stock in bankruptcy settlements.

After Gruber visited BancOhio's Columbus headquarters, they withheld their 1.3 million votes from Whitman.

Whitman never reached the votes needed to call a special meeting.

"My worst nightmare," he said, "is that I fight this thing through and win — and then discover there's no one there to buy it."

Gruber survived, and over the next two decades, his strategy of independence would pay off.

Change in Strategy

In 1977, Northern Life was sold for $52.5 million cash, partially used to repay Orion's outstanding bank debt. Gruber wanted to focus on property and casualty operations.

The most important acquisition came in 1978. Security Insurance Company of Hartford was purchased from Textron for $50 million cash, $12.5 million in subordinated notes and warrants to purchase about 1.9 million shares. Organized in 1841, the company provided the platform to expand into specialty P&C.

In 1981, Bankers National was sold to H.F. Ahmanson for $134 million. Proceeds repaid all outstanding debt and funded stock repurchases.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, Orion built a diversified specialty insurance platform through disciplined acquisition.

EBI Companies came in 1980, eventually becoming one of the top 25 U.S. writers of workers' compensation. Design Professionals Insurance Company (DPIC) followed in 1984, writing architects' and engineers' professional liability. Guaranty National Corporation brought nonstandard automobile insurance. Wm. H. McGee & Co. in 1995 added ocean marine, inland marine and cargo insurance.

Gruber exited mass-market insurance during the mid-1980s, moving away from personal auto, homeowners, general liability and commercial auto. Orion focused on specialty markets requiring complex risk management.

By 1993, Orion reported $68.8 million in net profits on $720 million in revenue, with return on equity of 17.5%, compared with single-digit returns at many P&C competitors.

Orion's 1996 annual report marked the 20th anniversary, which read:

Judge Harry Pregerson of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit recalls that there were many who thought the firm would not survive the reorganization process. Clearly, they were wrong.

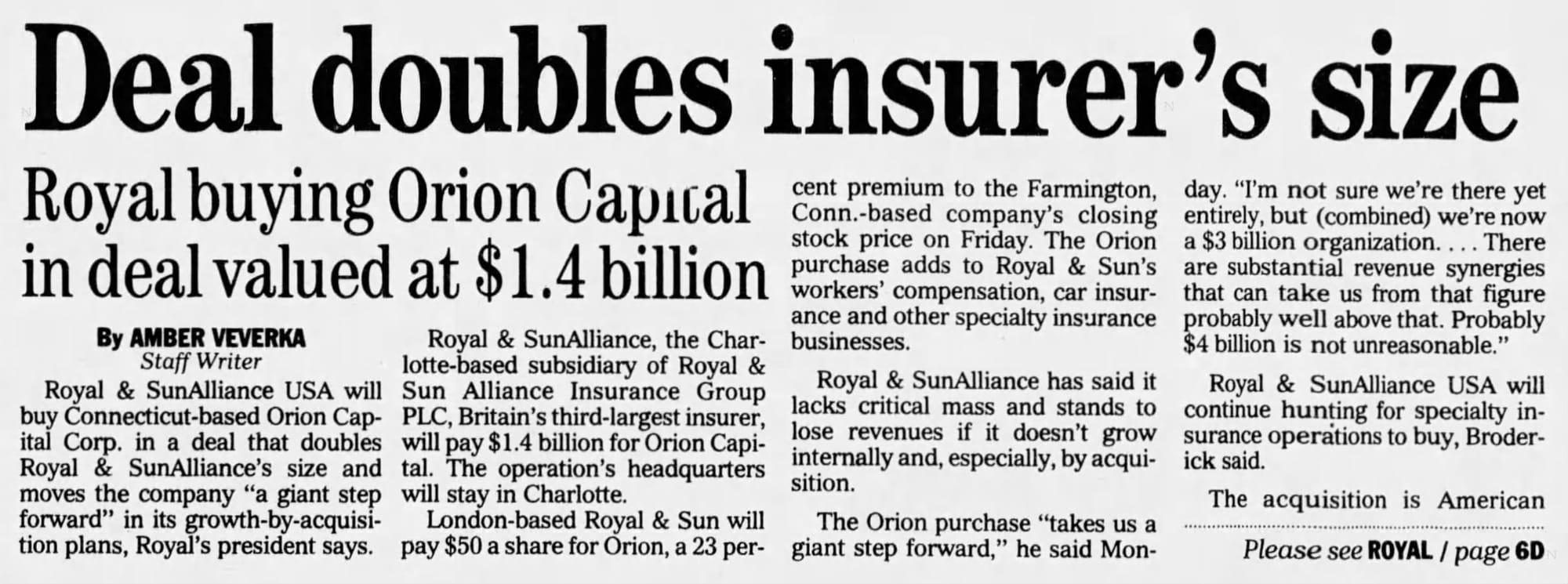

The Exit

When Gruber retired in December 1996, W. Marston Becker became chairman and CEO of Orion.

Becker accelerated acquisitions into specialty insurers: Grocers Insurance Group in 1998 for $36.25 million, Strickland Insurance Group and Unisun Insurance Company.

In July 1999, Royal & SunAlliance Insurance Group of London announced it would acquire Orion for $50 cash per share — approximately $1.4 billion including assumption of $460 million in debt.

The deal closed in November 1999.

Part IV: Lessons & Legacy

Dirks v. SEC

For Raymond Dirks, exposing the fraud was the beginning of a decade-long legal battle.

The SEC charged Dirks with violating securities laws by passing along Secrist's allegations to institutional clients, some of whom sold their Equity Funding shares before the fraud became public. The SEC censured him in 1974.

Dirks argued he had done nothing wrong. He had tried to get regulators to act. When they moved slowly, he kept investigating and shared what he learned. The sales by his clients, he argued, helped bring the fraud to light by driving down the stock price and attracting attention.

He appealed the censure. The case would take nine years to reach the Supreme Court.

In 1983, the court vindicated Dirks by a 6-3 vote.

Justice Lewis Powell's majority opinion established the "personal benefit" test for insider trading: an insider breaches fiduciary duty only when disclosing information for personal gain. Since Ronald Secrist disclosed information to expose fraud rather than for personal benefit, neither he nor Dirks violated securities laws.

The decision explicitly protected securities analysts, recognizing that,

Imposing a duty to disclose or abstain solely because a person knowingly receives material nonpublic information from an insider ... could have an inhibiting influence on the role of market analysts.

Auditing Reforms

The AICPA Special Committee on Equity Funding reported in February 1975,

Generally accepted auditing standards are adequate and customary audit procedures properly applied would have provided a reasonable degree of assurance that the existence of fraud at Equity Funding would be detected.

I.e., the problem was execution, not standards.

The executive in charge of the audit for Wolfson, Weiner — later acquired by Seidman & Seidman — was Solomon Block, who had his own office on Equity Funding's executive floor.

Up until the year the fraud collapsed, Block had never passed the tests required to become a certified public accountant.

One official involved in the investigation believed Block and others were "induced to look the other way, or not to look at all" rather than willingly participating.

"At present I see it more as a situation where if questions were raised in the work sheets, they wouldn't get answered," the official said. "The auditors would get a nonsensical answer, a non-answer, and let them go."

Even simple financial analysis would have brought up questions.

For example, 4Q 1970 profits were $11.1 million — almost twice the $5.8 million average for the previous three quarters. Securities commission revenues increased 40% in the same fourth quarter, to $5.3 million. Yet expenses to produce those commissions actually dropped, to $1.2 million.

This, in a year which Stanley Goldblum described to shareholders in his 1970 letter as,

...one of economic erosion throughout the American business community...The performance of the Company during the past two years has demonstrated that Equity Funding Corporation of America can perform well under various economic and stock market conditions.

It's easy to perform well when you get to write in the numbers.

EFCA is considered the first widely publicized computer crime, showing that software programs could be used for fraud. The Class 99 coding scheme showed how computers could systematically generate fake records.

But the AICPA committee cautioned against overstating the computer's role.

Much of the publicity about Equity Funding has characterized it as a 'computer fraud.' It would be more accurate to call it a 'computer-assisted fraud.' The computer was used, to a large extent, to manipulate files and create detail designed to conceal the fraud. Much of this processing was performed by personnel from outside the EDP department who were allowed access to computer hardware, software and files.

The computer made the fraud easier to execute but was not essential to the basic fraudulent acts.

The committee also wrote that "internal accounting and administrative controls at Equity Funding were so weak as to raise concern about the reliability of the accounting records." Customary procedures could have detected the fraud.

Conclusion

The EFCA fraud showed how the wrong incentives, weak internal controls and complacency can ruin a business.

Loeffler explained the fraud's survival this way,

Foremost, of course, were the lies, audacity and luck of the ringleaders. Of almost equal importance was the surprising ability of the originators of the fraud to recruit new participants over the years. Closely related was the moral blindness of those participants, including several who helped execute the scheme and then left the company, but remained silent.

But the bankruptcy restructuring showed that legitimate value can survive. Loeffler's quick reorganization saved viable assets. Gruber's strategic decision to exit mass markets and focus on specialty niches created competitive advantages.

Equity Funding Corporation of America never earned a legitimate profit. Yet what came after was able to compound at 19.8% for 23 years – a 65x return for the hypothetical buy-and-hold investor who held from the first day of trading through the Royal & SunAlliance acquisition.

One only had to hold through proxy fights, rejected takeovers, strategic pivots and two decades of acquisitions no one could have predicted.

Fidelity Corporation had a $23.2 million cost basis in Equity Funding. Had they held until 1999, they would have received $280 million in capital gains and dividends. Instead, they sold to Jay Pritzker at a 80% loss.

One of the greatest financiers of the century called it "a reasonable investment."

If you enjoyed the article, here's a movie on the Equity Funding fraud, staring James Woods.

Sources

- "The Money Men" Forbes, March 1, 1969

- "Insurance Fraud Charged By S.E.C. To Equity Funding", New York Times, April 4, 1973

- "Associates Find Goldblum Is Not Easy to Know", New York Times, April 21, 1973

- "22 Indicted By U.S. In Equity Scandal" New York Times, November 2, 1973

- "Those Daring Young Con Men of Equity Funding: The Full Story of an Incredible Fraud" by Wyndham Robertson, Fortune, August 1973

- Report of the Trustee of Equity Funding Corporation of America, Pursuant to Section 167(1) of The Bankruptcy Act, Robert M. Loeffler, Trustee, 1974, Volume I, II, III

- "Goldblum Enters Equity Guilt Plea", New York Times, October 9, 1974

- "The Great Wall Street Scandal" by Raymond L. Dirks and Leonard Gross, 1974

- 1975 Report of the Special Committee on Equity Funding: The Adequacy of Auditing Standards and Procedures Currently Applied in the Examination of Financial Statements, American Institute of Certified Public Accountants

- "Goldblum Among 6 Sentenced To Jail in Equity Funding Case" New York Times, March 19, 1975

- "The Impossible Dream - The Equity Funding Story: The Fraud of the Century" by Ronald L. Soble and Robert E. Dallos, 1975

- Matter of Equity Funding Corp. of America, 416 F. Supp. 132 (C.D. Cal. 1975)

- Gordon C. McCormick profile, Forbes, September 15, 1975

- "Salvage Job: How Equity Funding Escaped Liquidation, Against All the Odds" by William E. Blundell, Wall Street Journal, March 31, 1976

- In Re Equity Funding Corp. of Amer. SEC. Litigation, 416 F. Supp. 161 (C.D. Cal. 1976)

- "Pritzker Group Buys Orion Stock Sold by Fidelity" by Priscilla S. Meyer, Wall Street Journal, March 2, 1977

- "Once a fraud, now a forerunner" by George Gunset, Knight News Service, The Bradenton Herald, March 17, 1977

- "The Equity Funding Papers: The Anatomy of a Fraud" edited by Lee J. Seidler, Frederick Andrews, and Marc J. Epstein, 1977

- "Fracas Between Friends over Orion Capital Corp." by Hugh D. Menzies, Fortune, November 3, 1980

- Dirks v. SEC, 463 U.S. 646 (1983), United States Supreme Court

- "Focusing On Niche Insurance Markets Has Made Orion Capital" Hartford Courant, December 12, 1994

- "Deal Will Extend Royal's Reach" Business Insurance, July 18, 1999

- Agreement and Plan of Merger Among Orion Capital Corporation, Royal Group Inc., and RSA Merger Corp., 1999

- "Royal & SunAlliance Completes Orion Capital Buy" Property and Casualty, November 1999

- "Robert Loeffler, 79: Securities law Expert Cleaned Up Firm's Scandal" Los Angeles Times, June 21, 2002

- "Raymond Dirks, Whose Tipster Case Redefined Insider Trading, Dies at 89" New York Times, December 21, 2023

- Equity Funding Corporation of America Annual Reports and SEC Filings (1964–1973)

- Orion Capital Corporation Annual Reports and SEC Filings (1975–1999)

Member discussion